Using the practice of slow looking to tell musical stories

What is slow looking?

The phrase “slow looking” simply means taking intentional time to look closely at something. In her book Slow Looking: The Art and Practice of Learning Through Observation, Shari Tishman elaborates: “The term slow looking uses the vernacular of the visual, but it is important to emphasize that learning through prolonged observation can occur through all the senses” (Tishman 2). Unlike mindfulness, a state of being that also draws our focus to the present moment, we slow look with the intent to gain knowledge. Tishman’s book, bolstered by findings from her educational research, walks us through slow looking strategies and the positive impact slow looking makes in educational settings. Slow looking goes hand-in-hand with discovery learning, the process of learning through exploration and inquiry. Discovery learning is more engaging than a teacher explaining new concepts, and students better remember content when they construct an individualized understanding of the material.

Slow Looking in Action

Art is a natural setting for slow looking. Practice on the artwork below. You might ask yourself the following questions:

What do I see? What do I think about what I see? How do I feel about what I see?

What did I notice first? What did I notice after looking for a while?

What words come to mind as I look?

What more would I like to know about the artwork?

Do small parts create the big picture?

Does this remind me of something else?

How do I think this artwork was created? Were elements added in a certain order?

Ruth Asawa, Desert Plant, 1965

Using Slow Looking as a Springboard for musical Improvisation

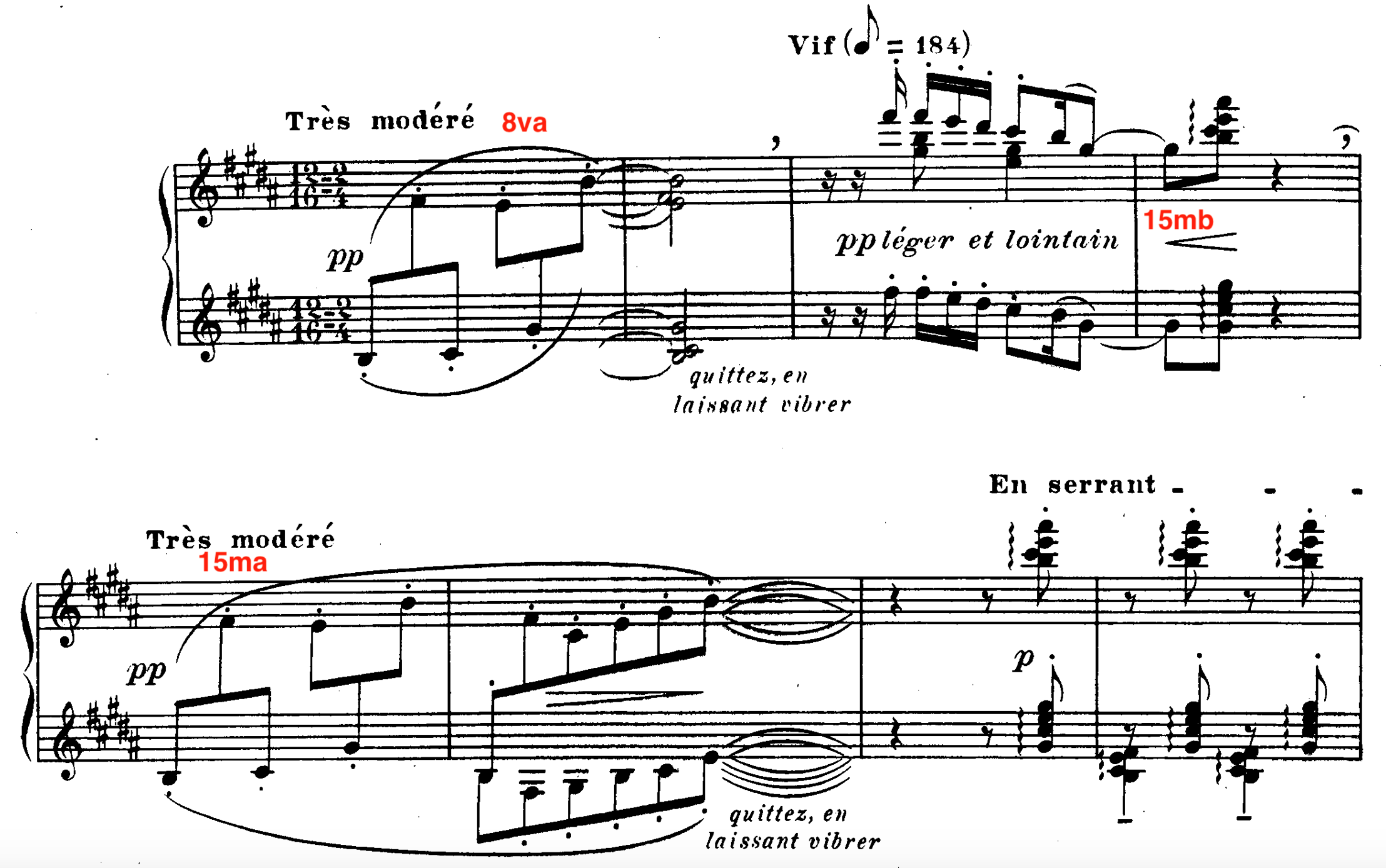

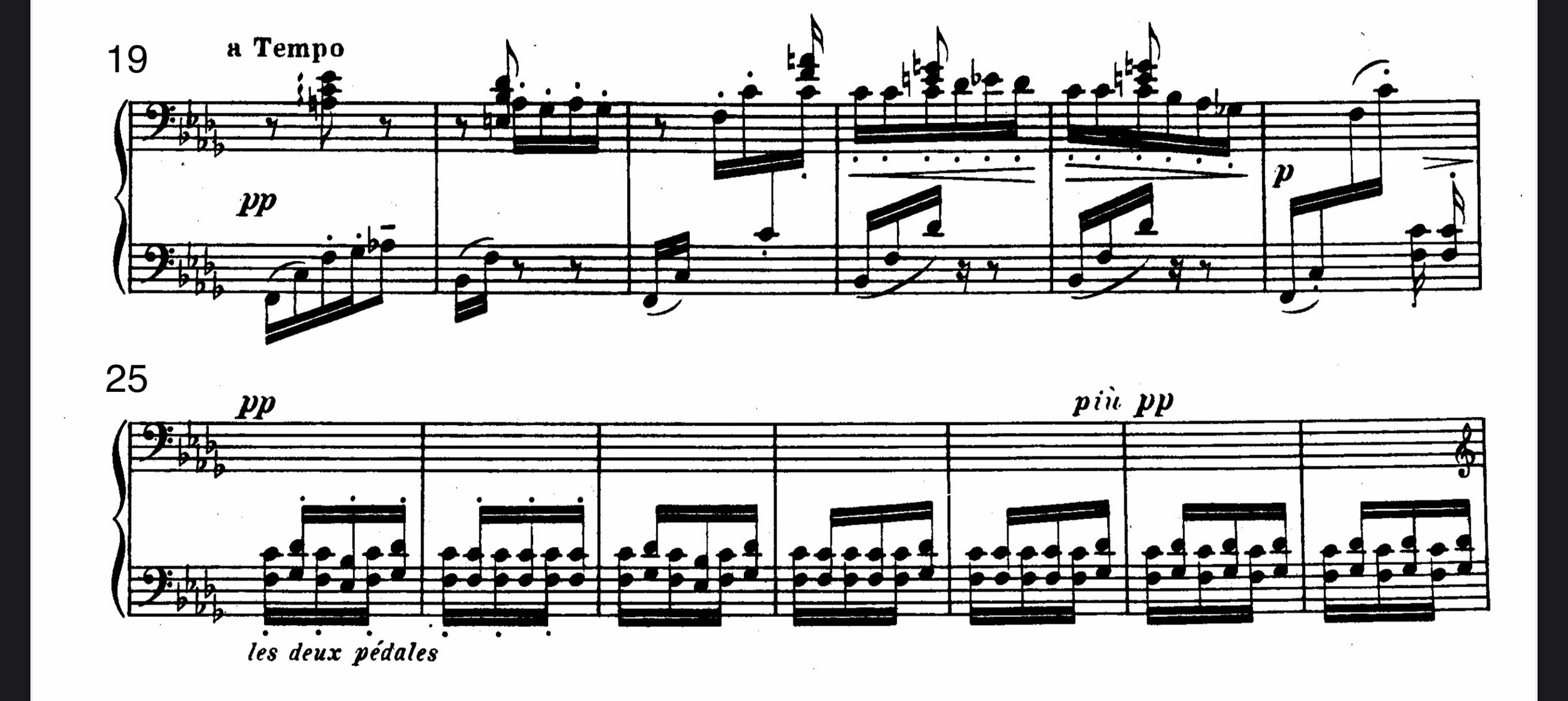

In a musical context, slow looking helps us understand the elements of music, their functions, and their purposes. Students train their brains to notice the layers and details that comprise a tapestry of sound. Slow looking lends itself well to two activities that have been met with enthusiasm in my studio: telling a story through music and improvising or composing new music using ideas from an existing piece. I’ve found that combining these two activities is an effective way to encourage students not only to listen slowly but also to improvise with less inhibition. By placing parameters—like improvising using rhythmic or tonal patterns we discovered through slow looking—students can improvise with clarity and confidence.

Part One: Introduction to a new piece

To encourage students to think about character and mood, perform a piece with the title hidden and have them guess what it might be about. Students use the practice of slow looking to find patterns and identify how the elements of music (e.g. melody, harmony, form, texture, dynamics) are at play in a given piece.

Next, we compare the title they brainstormed with the original title. It’s amazing how well students capture the essence of a piece! For example, “Floating,” “Dreaming,” “Soaring,” “Kite Flying,” and “Skating” are all common titles students give to “Gliding” by Elvina Truman Pearce. After thinking about the title, we learn the piece as the composer intended. Learning by rote is a natural opportunity for slow looking because listening is a crucial part of the learning process.

Part Two: Use the Title to Create a New Story

These are real-life examples from a recent lesson in which we studied “Gliding” by Elvina Truman Pearce. We slow listened to the piece to identify patterns and other characteristics, then learned to play it. In the following lesson, we did a creative activity.

I started by asking the following questions:

Who or what is gliding?

Where are they going? Why?

My student decided that Link from the Legend of Zelda was using his glider to travel to Kakariko Village to see Impa (another game character).

Then, I elaborated with these questions:

Are they close, or in the distance?

Does anything happen along the way?

When in the music do they arrive at their destination?

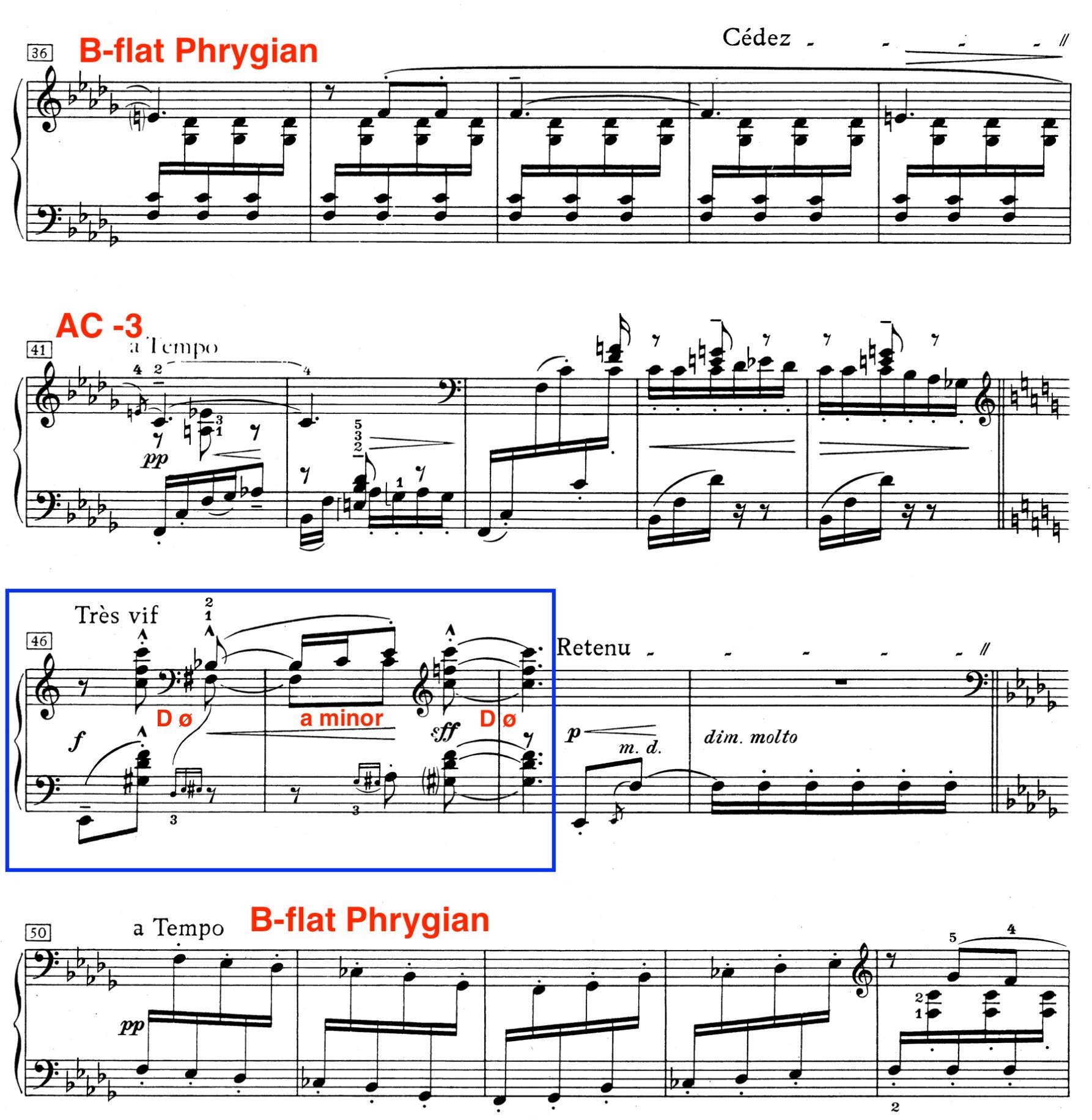

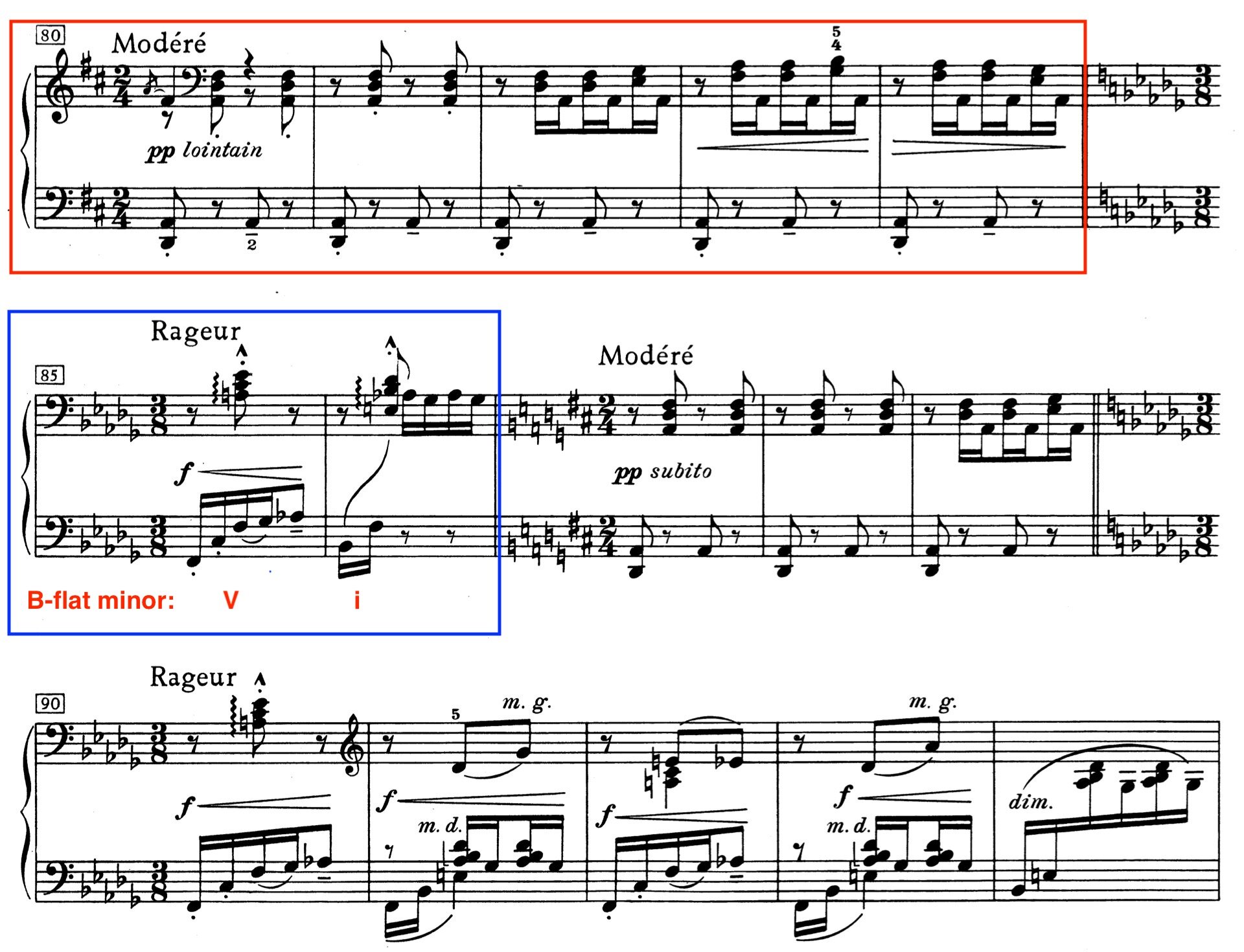

The observations the student made through slow looking appeared in many of his answers. For example, he decided that Link was far in the distance because the piece started softly and that the dotted half-notes in measures 5-6 (see below) sounded like the giant footsteps of monsters.

Finally, we thought about what musical aspects we might change to fit the story. This is what the student added:

he played mm. 5-6 loudly to signify the monsters

he added a ritardando in the last measure to show that Link was slowing down and landing gracefully

Part Three: Use Patterns to Improvise and Compose

These are the patterns this particular student identified:

The melody alternates between the CDE group on the white keys and a group of three black keys.

C’s, D’s, and E’s (white keys) are played as single notes while the black keys are struck together.

The melody always goes up.

Each phrase sounds like one upward line.

The hands work together to create the melody. Each hand is equally important.

The student then began improvising music by experimenting with note groups. I find that students are naturally inclined to create an “opposite” version of the piece they deconstruct. For example, this student began by playing the same melodic and rhythmic patterns but in a descending motion. From there, he more freely improvised using those patterns as inspiration.

The benefits of taking a slow look

Through her research on slow looking, Tishman identified four themes that appeared in students’ slow looking practices. Seeing with fresh eyes (interacting with the familiar as if newly discovered), exploring perspective (looking at things from multiple viewpoints), noticing detail (allowing observations to unfold from broad to specific) are three themes that deal with how students observed their surroundings. A fourth theme was philosophical well-being—students reported that slow looking reminded them of the important things in life. Students also noted that experiencing nature at a slow pace promoted a sense of well-being.

““When you look for a while, you become aware of how a thing might look to somebody else; you also become aware of your own lens...students come to an understanding of the multi-perspectival nature of knowing things in our world.” ”

Perhaps most importantly, slow looking intensifies the extramusical qualities that music lessons instill: an appreciation of beauty, an awareness of oneself and others, the ability to problem-solve thoughtfully and deliberately, and a willingness to slow down and see the goodness that surrounds us.

More Resources

Tishman, S. (2018). Slow looking: The art and practice of learning through observation. Routledge.

Thinking Strategies that Support Slow Looking

The Art of Slow Looking in the Classroom

In Praise of Slow by Carl Honore

Slow Looking by Peter Clothier

Slow Looking How-Tos by the National Museum of Women in the Arts